Chewang created artificial glaciers to provide water to the regions of Ladakh, has earned the title "The Ice Man of India"

Unlike most working class people, Chewang Norphel wasn't content with an ordinary existence aimed at sustaining a decent living. He saw a problem that affected his local community and he wanted to be a part of the solution. He used his engineering skills, decades of experience and a steely resolve to design and execute a series of artificial glaciers that solved the perennial problem of water shortages among farming communities of Ladakh.

Who is Chewang Norphel

On the surface, Chewang Norphel looks like any common inhabitant of Ladakh - soft-spoken, simple and humble, but when you dig a little deeper, you will find an intelligent and determined man with a very firm resolve to be a catalyst for change.

Born in a middle-class family in Ladakh, Chewang Norphel completed a diploma in engineering and joined the rural development department of Jammu and Kashmir as a civil engineer in Ladakh. This stint as a civil engineer in Ladakh opened up a path that made him realize and fulfill his life's calling.

Ladakh's Perennial Problem

Ladakh is a large swathing expanse of land which encompasses breathtaking scenic vistas, a distinct culture, hard-working people and a rugged unforgiving terrain. Scanty rainfall and freezing temperatures make it an arid land with a scarcity of water. The only sources of water are high up in the mountains in the form of glaciers that slowly melt in the summer and trickle down to the parched villages below giving them their seasonal supply of water.

Ladakh is primarily an agrarian economy with almost 80 percent of its inhabitants into farming. One of the major challenges that farmers of this region face is the lack of water during crucial stages of the crop cycle. Winter is too cold for any form of cultivation to bear fruit. The ideal time to grow crops in Ladakh is spring and summer — which begins in April. The farmers need water during this crucial initial stages of cultivation to irrigate and plough the dry frozen fields in order to prepare them for the sowing of seeds. But the problem was that the glaciers were still frozen in April and by the time they melted and filled the streams, it would be June, which was too late for any form of productive cultivation of crops. This perennial cycle of water shortages during the initial cycle of crop cultivation was a problem that plagued the farming communities of Ladakh.

The Eureka Moment

Chewang Norphel knew that the only solution to this problem was finding water in spring — April. In a power-starved region, with a jagged terrain, it was virtually impossible to pump water up from the rivers that flowed below at lower altitudes. Chewang had to find another way, and it was this underlying interest in finding a solution that eventually made him stumble upon an idea that would change the lives of his people.

It is customary in Ladakh to keep the water taps slightly open in winter to prevent the water from freezing and bursting the pipes. Chewang once noticed a stream of water from the water tap, outside his house, forming a solid sheet of ice over the sludgy soil underneath the trees, but quite strangely, the water flowed freely elsewhere in the surrounding areas. Immediately his grey matter started ticking — this was his eureka moment! He quickly realized that the water that was flowing freely from his tap only started freezing once its velocity slowed down over the sludgy soil underneath the shade of the trees.

Planning and Execution

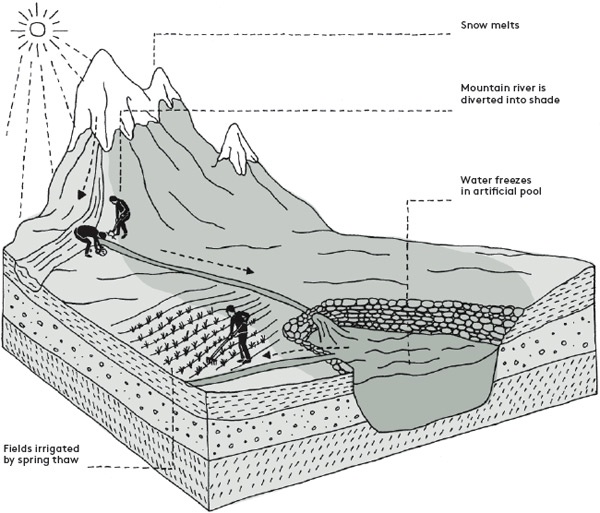

He had found the much-needed solution to the problem and now it was time for planning and execution. From June onwards, the melting glacial waters from streams that gets wasted by flowing into the rivers below. Chewang's ingenious plan was to divert this water into canals, catchment areas, and reservoirs where it would be stored until winter when it freezes to become an artificial glacier. This artificial glacier would then melt during spring, in April, giving farmers the much-needed water supply at the beginning stages of the crop cycle.

After a lot of trial and error, he fine-tuned the technique of making artificial glaciers. The natural glaciers were on top of the mountains at around 18,000 feet, the high altitude and low temperature prevented them from melting early around springtime. So Cheweng created his artificial glaciers closer to the villages at around 13,000 feet — the lower altitude hastened the melting process to begin in April.

Chewang's idea was brilliant in its simplicity: water is channeled from streams into the shadowy area of the mountains where it collects into natural depressions and catchment areas. His trick is to slow down the velocity of the water by constructing artificial retaining walls and obstructions in the form of bunds which hastens the freezing process. The water is slowed down further by placing narrow iron pipes in its path, which also enables the heat from the water to be quickly dissipated through the metal pipes. The end result is an artificial glacier at the other end. At the onset of Spring, melting water from these artificial glaciers are channeled back into the streams to feed the fields of farmers ready to begin cultivation in the villages below.

The Result

The first artificial glacier he built cost Rs 90,000 — this low-cost project was in stark contrast to the mega-budget dams elsewhere. Taking heart from this initial success, Cheweng Norphel went on to create 17 artificial glaciers across Ladakh. The windfall of his success has created a chain reaction of positivity in Ladakh: the agrarian economy has been boosted by the increase in agricultural production, the average income of the farmers have gone up, people no longer feel the need to migrate to cities in search of greener pastures — this has, in turn, helped keep the unique social fabric of Ladakh intact.

When Chewang Norphel initially proposed the idea of creating an artificial glacier — he was mocked, derided and termed crazy. But the thing that separates an achiever from an ordinary person is the fact that they don't allow the naysayers to deter them. They have confidence in their abilities and a firm faith in their mission which enables them to push past conventional boundaries to achieve their end goals.

Chewang's untiring efforts have paved the way for development and injected fresh life into the arid lands of Ladakh, which has, in turn, earned him the sobriquet — "The Ice Man of India".

The Padma Shri

In recognition of his accomplishments, he was bestowed with the Padma Shri in 2015 — India's fourth highest civilian award. This award was the cherry on a cake which is already filled with scores of other awards and recognition.

Chewang Norphel contribution to the people of Ladakh isn't just confined to building glaciers, he's also helped build bridges, irrigation canals, tanks, and other notable public works that have benefited the local inhabitants. Presently, Chewang Norphel continues to soldier on with myriad other projects and responsibilities.

Chewang Norphel fruitful life is best summarised in his own words: “As you sow, so you reap. There is no doubt that if one has strong determination and dedication, there is nothing impossible in the world. That is what I believe,” he says.

If you Like to contribute to this Page, Please Drop us a Mail.

hello@bookofachievers.com